A New Ted Lasso . . . from Korea

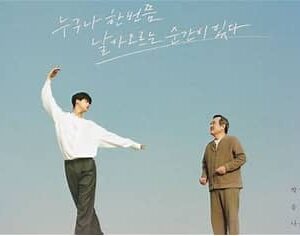

“Navillera” is a 12-episode Korean series, available on Netflix, that had — for us (Linda discovered it) — a message and power similar to the popular Apple series “Ted Lasso,” which ended last year after three seasons.

It’s different than Ted Lasso. It’s Korean, set in Korea with a Korean cast. In place of a soccer field, there’s a ballet studio. It’s not quite as funny as Ted Lasso, but it may be more poignant. Fewer F-bombs for sure. And unlike Lasso, which verges at the end toward melodrama by rendering the character of Rupert as a kind of Darth-Vadar, Navillera gives viewers a universalist vision of salvation.

But what it really has in common with TL is that every single character — from the central characters to one’s more at the periphery of the story — is in some way in need redemption. All of them, from young to old, need a mercy and grace that comes from beyond themselves. (Spoiler alert: I give most all of it away below.)

And in that respect, Navillera like Lasso, gives us a different take on ourselves and our world. Less the battlefield of contemporary life and politics and more the hospital, where everyone is in some way broken and in need of help and healing. As such it is, like Ted Lasso, an antidote to the often vicious and mean-spirited tenor of contemporary America, and to the violence-is-the-answer fare of both much of contemporary entertainment and politics.

Recently, the theologian Simeon Zahl drew the contrast between a Manichean and a Christian world-view. While few may know much of the ancient religion of Manicheanism, it is in many ways the world in which we live. For Manichaeans, there are two starkly opposed sides, each sure they are the force of good whole and unimpaired. Each seeks to wipe the other from the face of the earth. Redemption through violence. In contrast, the gospel does not envision the annihilation of all those who wreck havoc or pain on others but their redemption. The world, for the Christian, is less battlefield and more hospital.

And so it is in Navillera where the main character, an aged retiree, Mr. Sim (Shim Deok Chul), re-discovers and pursues his childhood passion for ballet. He does so against the odds, of age and of a diagnosis of Alzheimers, as well as the fervent opposition of his entire mortified family — who know nothing at that point of his illness. Like Ted in Lasso, Mr. Sim “believes,” most of all in other people and in the possibility that they, like him, will soar — if in their own way.

And so it is in Navillera where the main character, an aged retiree, Mr. Sim (Shim Deok Chul), re-discovers and pursues his childhood passion for ballet. He does so against the odds, of age and of a diagnosis of Alzheimers, as well as the fervent opposition of his entire mortified family — who know nothing at that point of his illness. Like Ted in Lasso, Mr. Sim “believes,” most of all in other people and in the possibility that they, like him, will soar — if in their own way.

This includes a gifted, but moody and diffident, young ballerino, Chae-Rok who reluctantly, and over his own protests, becomes Mr. Sim’s ballet teacher. At the time Chae-Rok is in a pretty deep funk, unsure of his talent and ready to throw in the towel. As much as he aids in Mr. Sim’s redemption, Mr. Sim does the same — even more so — for the petulant 23-year-old.

But not only him. Mr. Sim’s good-hearted if naive faith is communicated to all sorts of people who are in need of help and grace, from Chae-Rok’s own teacher, Mr. Ki, a cynical former ballet star forced out by injury to a bad-boy ex-soccer player, Ho-Beom, who beats up Chae-Rok, to avenge himself for the sins of Chae-Rok’s father, his one-time soccer coach who has been sent to prison for beating his own players.

Chae-Rok’s father finds his way too, from prison to provincial exile to a re-connection with his son. Mr. Sim’s granddaughter, meanwhile, suffers the brutal competitiveness of Korean business life to find her own happiness in the improbable world of a call-in radio show for the lost and lonely. There are many more characters, all in some way, bruised and battered by life, who experience a kind of redemption.

Chae-Rok’s father finds his way too, from prison to provincial exile to a re-connection with his son. Mr. Sim’s granddaughter, meanwhile, suffers the brutal competitiveness of Korean business life to find her own happiness in the improbable world of a call-in radio show for the lost and lonely. There are many more characters, all in some way, bruised and battered by life, who experience a kind of redemption.

There’s more than one Flannery O’Conner moment when grace is mediated through violence. For me the most stunning came when Mr. Sim’s eldest son heaped scorn upon his father — in true elder brother fashion (as in the parable of the Prodigal Son) — for studying ballet. Appalled by her son, Sim’s wife — who to that point had shared her son’s condemnation of Mr. Sim’s dream of ballet — forcefully batters her own son over the head with bok choy from her market bag.

“Navillera” is a Korean word that means, “like a butterfly.” While it may not be the best symbol of Christian redemption and resurrection, it is certainly one in which many have found meaning. Navillera tells the story of an old man, increasingly suffering the pain and ignominy of Alzheimers, who against-all-odds manages to fly “like a butterfly,” and of many other characters who emerge from their own tomb-like chrysalis to soar.

“Everyone you meet is fighting a great battle,” is a phrase of unknown provenance that a friend passed on to me and which I have incorporated into two of my recent paintings. Navillera reminds us of the truth of those words and of the power of compassion and faith.

![Anthony B. Robinson [logo]](https://www.anthonybrobinson.com/wp-content/themes/anthonybrobinson/images/logo.png)

![Anthony B. Robinson [logo]](https://www.anthonybrobinson.com/wp-content/themes/anthonybrobinson/images/logo-print.png)