The Whitman Dilemma

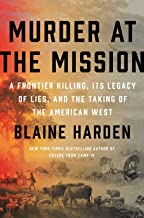

I’m reading Blaine Harden’s 2021 book, Murder at the Mission: A Frontier Killing, Its Legacy of Lies, and the Taking of the American West. Harden is an excellent researcher and writer. If you have not read his earlier work, A River Lost, on the Columbia River, I highly recommend it.

As the subtitle of Murder at the Mission suggests, Harden unmasks the myths surrounding the missionary-doctor, Marcus Whitman. Whitman has been made into a hero and martyr, his story used to fuel attacks on Indians and expropriation of their lands. Until this year his statue stood as Washington’s favorite son in the U. S. Capitol.

As the subtitle of Murder at the Mission suggests, Harden unmasks the myths surrounding the missionary-doctor, Marcus Whitman. Whitman has been made into a hero and martyr, his story used to fuel attacks on Indians and expropriation of their lands. Until this year his statue stood as Washington’s favorite son in the U. S. Capitol.

These revelations pose a challenge for a place like Whitman College, which is a very fine school. Two of our children are Whitman graduates. They got a great education in a wonderful, caring campus community. Both have enduring friendships from their Whitman years.

But what does a school like Whitman do when it discovers its namesake wasn’t the noble hero of yore, but someone quite different? Change the name altogether? Change the referent, from Marcus to say, Walt Whitman? Should that sound far-fetched it is what King County did in shifting from Rufus King to Martin Luther King Jr. Or does the school face into the truth and play a part in whatever acts of reconciliation and restitution may prove appropriate?

Similar questions face many individuals, institutions and really our whole nation. The story we learned of “How the West Was Won,” is at best one-sided. At worst it is, to use Harden’s words, “a legacy of lies.” Such stories, or mythologies, tend to be a way we elevate ourselves and enhance our own self-image. “I am a descendent of . . . ”

It won’t surprise you that I think theology is relevant here. If we are justified before God, to ourselves and to other people by our good lives and works or the good lives/ works and nobility of our forebears, stories like the one Blaine Harden tells are hard to take. They threaten our self-image. If, on the other hand, you understand yourself as a sinner who stands in need of grace and is justified by God’s grace and mercy alone, then it becomes possible to look honestly at the past and at yourself. Our stories and lineage, like we ourselves are a mix of good and ill, decency and deception.

The Christian doctrine here is simul justus et peccator, meaning we are simultaneously justified, or “saved,” and sinful. We are all both saint and sinner.

Whitman College’s origins, like many fine liberal arts schools, are religious. Specifically, Christian and Congregational. But I’m not sure this theological perspective or resource remains available to or at Whitman College today. Like many such colleges, connections with origins in Christian faith and tradition have been held loosely, even severed entirely in the name of pluralism and inclusivity, in recent decades.

That’s regrettable. When we lack a story or theological world-view that allows us to see ourselves, and our forebears, more clearly and honestly, we tend to fall back on self-justification, pointing to our record of achievement and service. “Okay, so maybe Marcus Whitman was a mediocre missionary, and his missionary sidekick, Henry Spalding, who was a liar and con-man — but we’re nothing like that!”

But in the end, the apostle Paul was right. “All have sinned, all have fallen short of the glory of God.” Starting from there, we can take a more honest look at our history and our present.

![Anthony B. Robinson [logo]](https://www.anthonybrobinson.com/wp-content/themes/anthonybrobinson/images/logo.png)

![Anthony B. Robinson [logo]](https://www.anthonybrobinson.com/wp-content/themes/anthonybrobinson/images/logo-print.png)